Shameless

What's below started out as an e-mail reply to an essay by a colleague. The essay took the position that deficits don't matter, not very much anyway. For some reason, this touched a nerve with me. And I composed and fired off the response below. I've edited it a bit. But it's still a little cruder and heavy handed that I'd normally publish. However, I think the crux of it is right. If you've got comments, fire away. regards, Dan Deficits don’t matter? Or do they? The first issue you need to clear up when answering this question is if “deficit” refers to total U.S. debt (public/household/corporate) as % of GDP or just Federal debt. Households and corporations borrow in the open market. And although rates are manipulated by the Fed, the risk they take is their own, i.e. bankruptcy. Bankruptcy laws have changes and made it easier for people or corporations to go bankrupt without really paying the price. It might be a good idea to bring back debtor's prisons. But still, at least in non-public borrowing there's a price to be paid for being a bad credit risk, either in bankruptcy itself, or having to pay higher interest rates. You get kicked out of business and it becomes harder for you to waste someone else's capital again. The market spots a failure. The point being that the household/corporate debt as a percentage of GDP is less important, in my mind, because it reflects choices people willingly make with their own money (or with shareholder money). In each case, the borrower is held accountable by the market place. Shareholders punish stocks that waste capital (eventually). They sell them and move on to more efficient enterprises that don’t waste their money but multiply it. And I suspect at the household level, homeowners who borrowed cheap to buy too much house will soon owe more than they own. All of which is fine. No one holds a gun to your head and tells you to buy a house or Amazon.com and 900 times earnings. It’s simple risk and reward, resolved by market forces. Government borrowing is different. The government doesn't borrow money to create income-producing assets or make capital investment (home ownership). We’ll exclude for now the subject of government investment in basic infrastructure. For purposes of this discussion, let’s say that, for the most part, the government borrows to simply redistribute income, to make transfer payments. It does not create wealth. Because the government pays off its bonds with tax revenues (which it collects at the barrel of a gun) it's able to borrow at much lower interest rates than the private sector. And it's also able to run regular deficits as a percentage of its income because the income itself is...virtually guaranteed. No one "chooses" government services. The government imply collects its revenues through confiscation, a nice business if you can get it (or if you command the army and the police.) This has an obvious effect: it encourages even more government borrowing to distribute more money to get more votes to spend more money on the people who voted you in. It's nothing new. Neither is it sustainable. At what point does it become unsustainable? I suppose a government could borrow over 100% of GDP if there were people willing to own the bonds. But my main argument here is that an economy in which government borrowing becomes an increasingly large portion of GDP is one that's creating less wealth than it could. The economy grows less fast than it might. That means fewer tax revenues, fewer jobs, and fewer growing incomes. This takes its toll over time, but you see its net effect in socialist Europe. The pie gets smaller. ( It doesn't, "Make the pie higher," as Bush once said.) Worst of all, government deficits are addictive to shameess pandering politicians. Take your pick from either side of the aisle. Which brings me to point number two... Discretionary vs. Non-discretionary Spending: No Way Out Over 70% of 2004's $2 trillion in federal spending is non-discretionary. It's spending mandated by law, including Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, and interest on the debt. There are fixed, legislated growth rates in non-discretionary spending, that can only be reduced by an act of political will (not likely). Barring a political magnetic pole reversal, federal spending is only going to keep growing. And if spending grows faster than income...deficits will only get larger. And by the way, the Medicare prescription drug benefit grew in cost by another $143 billion since November. It's now going to cost over $500 billion over ten years...or nearly 6% of GDP. Optimists suggest we can (a) grow our way out of it or (b) cut discretionary spending. Maybe. But defense and homeland security make up the bulk of discretionary federal spending. And the President has budgeted for 7% INcreases on both those next year, not decresases. Plus, that doesn't even include an extra $40 to $50 billion to pay for continuing operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Those aren't included in the budget submitted, although at $407 billion and 4% of GDP, its still an impressive increase in an area where we're told we could save money. Bottom line: the war on terror, like the cold war and like world war two, is a blank check to increase discretionary spending. And since the war has no definable ending...the increases are seemingly infinite. If discretionary spending ain't going down, and non-discretionary spending CAN"t go down, there's only one choice left: MEGA GROWTH in TAX REVENUES (hint, hard to achieve by cutting taxes) But what about growing out of our deficits? A federal deficit of 5% of GDP doesn't seem so bad, historically speaking. Why not 10%? 15% 20%? Again, the point is that this is not simply a mathematical question of sustainability, but one of how wealth is created. I'd say that when the available savings of the world (since the U.S. economy is not creating a lot of savings for its own pool of investment capital) go increasingly to simple income redistribution programs and not to new investment or job creation...the long-term ability of the economy to create capital and wealth is hollowed out. The world is paying for American retirement and healthcare and getting less than 5% for the privilege. How long will that last? Government borrowing diverts savings away from productive investment and towards simple wealth redistribution. Over time, capital formation slows down...and so does business investment...as has happened here in Europe. My third and final, and most serious bone of contention is moral. The more content we are with regular government deficits, the less responsible we become for ourselves. Borrowing increases actual indebtedness...but it increases dependence, too. People get used to expecting things to be paid for and provided by the government. Once created and funded, how many government programs have gone away? Very few, if any. They develop a constituency of bureaucrats who need them for jobs or of tax payers who reap the booty of the wealth distribution. The whole exercise in representative government then becomes a shameless debasing game of looking out for your piece of the loot at the expense of your neighbors and friends...and your children and grandchildren. At root this is an argument that public debt (debt taken out in the name of the people and not by an individual or corporate risk taker) quickly becomes a shallow political ploy to win elections. This becomes corrosive to private morality. As an example, take the heat waves in France this past summer. Fifteen thousand people who survived the depression and World War two died in their homes or unattended in hospital beds from the heat. Their doctors, neighbors, and children were at the beach, on vacation, confident that the tax dollars they spent were taking care of their loved ones. When Chirac gave his speech to the nation addressing the human catastrophe, he said that no one person was to blame, but that all of France was to blame. That's pretty convenient. All of France means not me and not you but all of us. So let's just do better next time. Maybe in their private moments the children and neighbors of these people DO blame themselves for subcontracting their responsibility to take care of their elders to the government. And then again, maybe they DON'T. Maybe the cumulative affect of letting the government become the moral middleman is that you don't care about anyone but yourself anymore. You care about your job, your leisure time, your life. You work less, have fewer children, and stop believing in God or anything more than yourself. It may be a stretch...but I think it all starts the moment we accept that spending more than we earn--as a nation, through our government-- is morally tolerable. If it's not good for a private household to do it, not good economically and not good morally, why would it be better for the government to do it? Non-discretionary spending is busting the budget. Seventy percent of government spending is non-discretionary promises to pay for things the government does now, but which used to be done by families, churches, or the private sector. We have locked in these promises and have closed the discussion of whether we ought tom or can afford to keep making them. This view also suggests that we shouldn't treat our economics as mere mathematics. Economics used to be called moral philosophy. The study of the choices people made with their money couldn't be separated from whether the choices themselves were "good." The market judges "good" by whether the good or service you provide makes things better for people. If it does, you get rewarded for your risk. If it doesn't, generally, you fail. Debt isn't immoral per se. But taking on debt you have no intention of repaying is. And doing in the name of the "State" or the "people" may give you the political cover you need to explain away your recklessness. You disguise it as concern for the "public good" or for "society." But morally speaking, when you sanction it, you're contributing to the impoverishment of your economy and the debasement of your own morality.

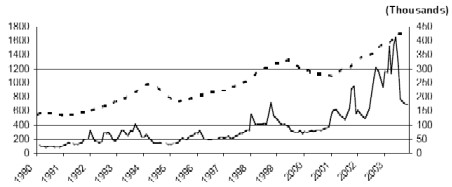

The main point is that the VIX measures fear. It’s often called “The Fear Gage.” And what you can tell from my chart earlier (and the one above), is that bull markets in fear lead to bear markets in stocks.

If that’s all the VIX was useful for, it would be very useful indeed. You’d have a great way to call market tops and bottoms. But in a few months, you’ll be able to do more than that.

CBOE has applied for a listing for the VIX to trade on the new CBOE Futures Exchange. You’ll be able to trade the VIX. Unfortunately, it will be on the futures market. So you’ll be trading options on futures (something my friend Sue Rutsen at Fox Investments does very well.)

But aside from trading options on futures rather than a straight up option, adding the VIX to your toolbox is a good idea if you have a big bullish bet in the market. A call on the VIX is essentially a bet that volatility will increase and that, if the historical relationship holds, stocks will fall. So, by owning VIX calls…you own a kind of bear-market insurance.

There are other ways to do this of course, like through long-dated put options on the indexes. But what’s nice about the VIX is that it’s so directly correlated to the S&P. So a S&P bull can own VIX calls and be reasonably confident that a fall in the S&P will be hedged by a rise in the VIX.

I’d recommend using the VIX as a way to make directional bets, i.e. the VIX is going to rise or fall. Right now, it’s a simple bet. The VIX is coming off historic lows. It’s got a lot of up to go. I’d buy calls.

None of this makes the market less risky. But what’s interesting about a listing for the VIX is that it puts pretty sophisticated hedging at the fingertips of retail investors like you and me. You can take a few simple positions in a Rydex fund, in the VIX, or in broad market index puts, and at least take out, at a pretty cheap price, an insurance policy on your buy-and-hold positions.

Insurance probably isn’t the right word, because no one is going to give you your money back if you lose it being long stocks. But now, you can make money on market declines, and you can do it relatively cheaply. That’s progress.

The main point is that the VIX measures fear. It’s often called “The Fear Gage.” And what you can tell from my chart earlier (and the one above), is that bull markets in fear lead to bear markets in stocks.

If that’s all the VIX was useful for, it would be very useful indeed. You’d have a great way to call market tops and bottoms. But in a few months, you’ll be able to do more than that.

CBOE has applied for a listing for the VIX to trade on the new CBOE Futures Exchange. You’ll be able to trade the VIX. Unfortunately, it will be on the futures market. So you’ll be trading options on futures (something my friend Sue Rutsen at Fox Investments does very well.)

But aside from trading options on futures rather than a straight up option, adding the VIX to your toolbox is a good idea if you have a big bullish bet in the market. A call on the VIX is essentially a bet that volatility will increase and that, if the historical relationship holds, stocks will fall. So, by owning VIX calls…you own a kind of bear-market insurance.

There are other ways to do this of course, like through long-dated put options on the indexes. But what’s nice about the VIX is that it’s so directly correlated to the S&P. So a S&P bull can own VIX calls and be reasonably confident that a fall in the S&P will be hedged by a rise in the VIX.

I’d recommend using the VIX as a way to make directional bets, i.e. the VIX is going to rise or fall. Right now, it’s a simple bet. The VIX is coming off historic lows. It’s got a lot of up to go. I’d buy calls.

None of this makes the market less risky. But what’s interesting about a listing for the VIX is that it puts pretty sophisticated hedging at the fingertips of retail investors like you and me. You can take a few simple positions in a Rydex fund, in the VIX, or in broad market index puts, and at least take out, at a pretty cheap price, an insurance policy on your buy-and-hold positions.

Insurance probably isn’t the right word, because no one is going to give you your money back if you lose it being long stocks. But now, you can make money on market declines, and you can do it relatively cheaply. That’s progress.

Double Top, Triple Top...And?

Double Top, Triple Top...And?

Pretty clear. The less investors care about risk (VIX), the more Internet stocks they buy (IIX). What kind of risk is being taken here? Here are the top five holdings of IIX and their respective p/e ratios.

1. Qualcomm (QCOM) -- p/e of 49

2. Broadcom (BRCM) -- no earnings, but it's losing about $9.90/share

3. eBay (EBAY) -- p/e of 99

4. Juniper (JNPR) -- p/e of 188

5. Symantec (SYMC) -- p/e of 39

But aside from simple market/value risk...there's plenty of Marco risk. Stephen Roach had an excellent report from the World Economic Forum at Davos. The outsourcing issue is beginning to rankle a lot of people...mostly because it's starting to cost high-paying white collar jobs as well as high-paying manufacturing jobs.

He also makes the point that globalization is a destructive as well as a creative process. The upside for Americans, the rest of the world is producing astonishingly cheap goods for us to consume. The downside, Americans who used to make their living making this goods or providing these services are out of a job.

The net result is a return to protectionism...which our fearless political idiot leaders in Washington have no shame in returning to right away. As the campaign heats up this spring and summer...don't be surprised if the candidates try to outdo each other on ways to save American jobs, the American farm, and the American worker. Globalization is generally good for us, except when it's not.

From Roach (emphasis added is mine):

"The fifth theme I took away from Davos this year is the most worrisome of the lot, the mounting risk of a protectionist endgame. Former senior policy makers were especially worried about the ramifications of the rapid emergence of China and India. One argued that the pace of change, to say nothing of the scale and scope of such development, shatters any semblance of globalization's status quo. Another stressed the precedent of agriculture as an example of how badly the modern world has bungled secular declines in core economic activities; the fear is that today's protectionist web of farm subsidies could well be a harbinger of what's to come in the aftermath of the secular decline in manufacturing. Needless to say, pressures on services would only exacerbate this risk.

"Concerns over mounting protectionist sentiment in the US Congress were especially evident in Davos. Japan and the US have led the way in China bashing, and there is fear that Europe is about to follow suit. History does not speak well of the world's ability to cope with large entrants in the arena of global commerce. The darkest fears of Davos pertained to the lessons of such episodes in history and how they may apply to a world that is now attempting to cope with the rapid emergence of China and India, nations that collectively account for more than 35% of the world's population. Trade liberalization, the mainstay of globalization, cannot be taken for granted in this climate.

"Yes, there was an improved tone in Davos this year. But it came off of easy comparisons, a world that a year ago was weak economically and on the brink of a serious war. A rebound in the global economy and world financial markets has certainly tempered any residue of angst -- at least for the time being. Moreover, there was a nearly unanimous view that nothing bad could happen to this US-centric world between now and the November 2 American presidential election. At the same time, there was a palpable sense of unease as to what might then follow in the post-election climate. This tug-of-war between a constructive near-term outlook and the ever-mounting strains of globalization was the essence of this year's debate at Davos. "

Pretty clear. The less investors care about risk (VIX), the more Internet stocks they buy (IIX). What kind of risk is being taken here? Here are the top five holdings of IIX and their respective p/e ratios.

1. Qualcomm (QCOM) -- p/e of 49

2. Broadcom (BRCM) -- no earnings, but it's losing about $9.90/share

3. eBay (EBAY) -- p/e of 99

4. Juniper (JNPR) -- p/e of 188

5. Symantec (SYMC) -- p/e of 39

But aside from simple market/value risk...there's plenty of Marco risk. Stephen Roach had an excellent report from the World Economic Forum at Davos. The outsourcing issue is beginning to rankle a lot of people...mostly because it's starting to cost high-paying white collar jobs as well as high-paying manufacturing jobs.

He also makes the point that globalization is a destructive as well as a creative process. The upside for Americans, the rest of the world is producing astonishingly cheap goods for us to consume. The downside, Americans who used to make their living making this goods or providing these services are out of a job.

The net result is a return to protectionism...which our fearless political idiot leaders in Washington have no shame in returning to right away. As the campaign heats up this spring and summer...don't be surprised if the candidates try to outdo each other on ways to save American jobs, the American farm, and the American worker. Globalization is generally good for us, except when it's not.

From Roach (emphasis added is mine):

"The fifth theme I took away from Davos this year is the most worrisome of the lot, the mounting risk of a protectionist endgame. Former senior policy makers were especially worried about the ramifications of the rapid emergence of China and India. One argued that the pace of change, to say nothing of the scale and scope of such development, shatters any semblance of globalization's status quo. Another stressed the precedent of agriculture as an example of how badly the modern world has bungled secular declines in core economic activities; the fear is that today's protectionist web of farm subsidies could well be a harbinger of what's to come in the aftermath of the secular decline in manufacturing. Needless to say, pressures on services would only exacerbate this risk.

"Concerns over mounting protectionist sentiment in the US Congress were especially evident in Davos. Japan and the US have led the way in China bashing, and there is fear that Europe is about to follow suit. History does not speak well of the world's ability to cope with large entrants in the arena of global commerce. The darkest fears of Davos pertained to the lessons of such episodes in history and how they may apply to a world that is now attempting to cope with the rapid emergence of China and India, nations that collectively account for more than 35% of the world's population. Trade liberalization, the mainstay of globalization, cannot be taken for granted in this climate.

"Yes, there was an improved tone in Davos this year. But it came off of easy comparisons, a world that a year ago was weak economically and on the brink of a serious war. A rebound in the global economy and world financial markets has certainly tempered any residue of angst -- at least for the time being. Moreover, there was a nearly unanimous view that nothing bad could happen to this US-centric world between now and the November 2 American presidential election. At the same time, there was a palpable sense of unease as to what might then follow in the post-election climate. This tug-of-war between a constructive near-term outlook and the ever-mounting strains of globalization was the essence of this year's debate at Davos. "