Tomorrow, in the weekly edition of SI, I'll have concise housing roundup. As I write, 30-year fixed mortgage rates are again making a new low. And earlier today,

Fannie Mae raised its forecast for mortgage loan originations in 2004 from $1.9 trillion to $2.43 trillion--which would make it the third largest year for new mortgage loans in history.

Of course to make those loans, Fannie will have to sell bonds. And to sell bonds it will take buyers. And while European central banks unloaded GSE bonds last year, there are still plenty of buyers. Fannie reported today that it sold $2 billion worth of 5-year bonds today, yielding 3.22%. 52% of the offering was scooped up by Americans buyers (J.P. Morgan perhaps), while Asia bought 40%, Europe 7%, and various others 1%.

That's pretty robust demand, although there's a big difference between buying $2 billion in bonds and $2.43 trillion. However I remain steadfastly bearish on the GSEs and the housing sector. I've posted John Snow's comments below because he uses the phrase, "

orderly wind down of affairs of a GSE that gets into serious financial trouble." That's on the heels of Greenspan talking about systemic risk.

Why are the nation's top policy makers talking about the GSEs with such provocative language? What do they know that we don't know? Are they trying to send the market a signal? I think they are. And I'm selling Fannie and Freddie.

But the GSEs aren't the only one with debt problems. And they've been able to unload that debt on willing buyers. Compare that to today's lukewarm reception to an auction of $11 billion worth of U.S. Treasury bonds yielding 3.75%. "

People swallowed this auction like it was castor oil,'' said Drew Matus, a senior economist at Lehman Brothers, quoted in a Bloomberg article.

Today's auction comes off of yesterday's government auction of $16 billion in five year notes. And both auctions come against the backdrop of a government seeking to borrow $177 billion this quarter alone to finance a half a trillion dollar trade gap.

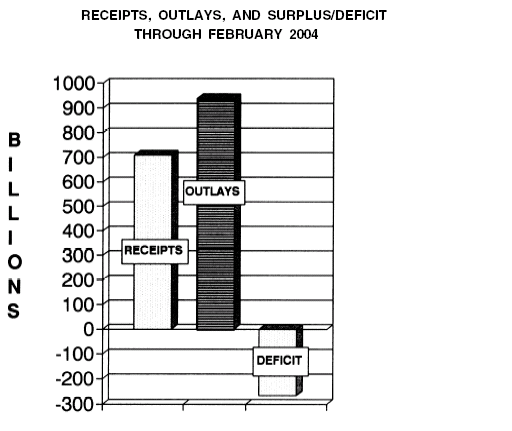

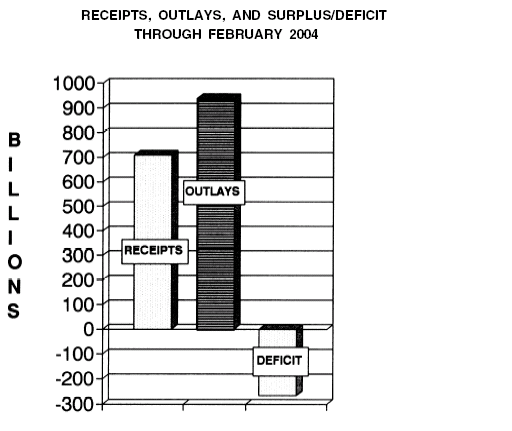

Incidentally, as I write this, I got my monthly e-mail bulletin from the Treasury revealing that... you guessed it, the government ran a deficit again in February. Have a seat though before you read it, okay. Ready? Here comes...

$96 Billion. Billion with a "B."

That's largest one month deficit in the last two fiscal years. In fact, I've just done a quick scan of historic data on the Treasury site, and I believe that's the largest single month government deficit in the history of the Republic. A few facts to go with it:

*$15. 2 billion of the total went directly to interest on existing public debt. In other words, 8% of the government's outlays were just to pay lenders.

*Spending, for the first five months of this fiscal year compared to the first five of last year, has grown 4.2%, from $898 billion last year to $937 billion this year

*The deficit for the first five months of this fiscal year compared to last year is 16.4% greater--from $194 billion last year to $226 billion this year.

Here's the picture folks:

This won't be good for the dollar. It won't be good for stocks. And it probably won't be good for bonds prices either. It means more supply of debt with demand already half-hearted (regardless of what the Secretary says below about the "quality" of U.S. government paper.)

In fact, the only green I see on my screen right now is for bond yields (TNX, FVX, TYX) and the VIX, which is up 12% as of this writing to 18.6. Not so complacent anymore. The worm has turned...

Treasury Secretary John Snow Remarks to America's Community Bankers Association Government Affairs Conference March 9, 2004. Emphasis added is mine.

"

GSEs are able to borrow at rates that are lower than their other financial competitors, other financial institutions, because they are perceived by many in the marketplace to have a relationship with the government, they are perceived to have a government guarantee.

"Since Fannie and Freddie trade at very narrow spreads to the very best paper in the world, which is the U.S. Treasury, they have become enormous entities, and they are growing at a very, very rapid rate. The debt levels they are issuing are sizable relative to the economy of the United States.

"

To put it into perspective, the U.S. Government debt held by the public is about $3.6 trillion; the GSEs now totals about $2.4 trillion and when you are that big you have potential significant impacts on financial markets.

"Our goal at the Treasury Department is to promote the health and strength of the housing finance markets together with the health and strength of the U.S. financial system. In the United States' economy today, the two are closely related.

"We also want to ensure that GSEs are living up to the highest standards of corporate responsibility.

"

We don't believe in a 'too big to fail' doctrine, but the reality is that the market treats the paper as if the government is backing it. We strongly resist that notion.

"You know that there is that perception. And it's not a healthy perception and we need to disabuse people of that perception. Investments in Fannie and Freddie are uninsured investments.

"That is why

clear receivership authority is necessary Because there is investment risk, full and flexible authority for the orderly wind down of affairs of a GSE that gets into serious financial trouble is vitally important for market stability.

"Blind faith in non-existent guarantees cannot be an acceptable substitute."

Amen.

OEX Bullish percentage chart breaking down.

OEX Bullish percentage chart breaking down.

And put buyers out in force, via the put/call ratio.

And put buyers out in force, via the put/call ratio.

This won't be good for the dollar. It won't be good for stocks. And it probably won't be good for bonds prices either. It means more supply of debt with demand already half-hearted (regardless of what the Secretary says below about the "quality" of U.S. government paper.)

In fact, the only green I see on my screen right now is for bond yields (TNX, FVX, TYX) and the VIX, which is up 12% as of this writing to 18.6. Not so complacent anymore. The worm has turned...

Treasury Secretary John Snow Remarks to America's Community Bankers Association Government Affairs Conference March 9, 2004. Emphasis added is mine.

"GSEs are able to borrow at rates that are lower than their other financial competitors, other financial institutions, because they are perceived by many in the marketplace to have a relationship with the government, they are perceived to have a government guarantee.

"Since Fannie and Freddie trade at very narrow spreads to the very best paper in the world, which is the U.S. Treasury, they have become enormous entities, and they are growing at a very, very rapid rate. The debt levels they are issuing are sizable relative to the economy of the United States.

"To put it into perspective, the U.S. Government debt held by the public is about $3.6 trillion; the GSEs now totals about $2.4 trillion and when you are that big you have potential significant impacts on financial markets.

"Our goal at the Treasury Department is to promote the health and strength of the housing finance markets together with the health and strength of the U.S. financial system. In the United States' economy today, the two are closely related.

"We also want to ensure that GSEs are living up to the highest standards of corporate responsibility.

"We don't believe in a 'too big to fail' doctrine, but the reality is that the market treats the paper as if the government is backing it. We strongly resist that notion.

"You know that there is that perception. And it's not a healthy perception and we need to disabuse people of that perception. Investments in Fannie and Freddie are uninsured investments.

"That is why clear receivership authority is necessary Because there is investment risk, full and flexible authority for the orderly wind down of affairs of a GSE that gets into serious financial trouble is vitally important for market stability.

"Blind faith in non-existent guarantees cannot be an acceptable substitute."

Amen.

This won't be good for the dollar. It won't be good for stocks. And it probably won't be good for bonds prices either. It means more supply of debt with demand already half-hearted (regardless of what the Secretary says below about the "quality" of U.S. government paper.)

In fact, the only green I see on my screen right now is for bond yields (TNX, FVX, TYX) and the VIX, which is up 12% as of this writing to 18.6. Not so complacent anymore. The worm has turned...

Treasury Secretary John Snow Remarks to America's Community Bankers Association Government Affairs Conference March 9, 2004. Emphasis added is mine.

"GSEs are able to borrow at rates that are lower than their other financial competitors, other financial institutions, because they are perceived by many in the marketplace to have a relationship with the government, they are perceived to have a government guarantee.

"Since Fannie and Freddie trade at very narrow spreads to the very best paper in the world, which is the U.S. Treasury, they have become enormous entities, and they are growing at a very, very rapid rate. The debt levels they are issuing are sizable relative to the economy of the United States.

"To put it into perspective, the U.S. Government debt held by the public is about $3.6 trillion; the GSEs now totals about $2.4 trillion and when you are that big you have potential significant impacts on financial markets.

"Our goal at the Treasury Department is to promote the health and strength of the housing finance markets together with the health and strength of the U.S. financial system. In the United States' economy today, the two are closely related.

"We also want to ensure that GSEs are living up to the highest standards of corporate responsibility.

"We don't believe in a 'too big to fail' doctrine, but the reality is that the market treats the paper as if the government is backing it. We strongly resist that notion.

"You know that there is that perception. And it's not a healthy perception and we need to disabuse people of that perception. Investments in Fannie and Freddie are uninsured investments.

"That is why clear receivership authority is necessary Because there is investment risk, full and flexible authority for the orderly wind down of affairs of a GSE that gets into serious financial trouble is vitally important for market stability.

"Blind faith in non-existent guarantees cannot be an acceptable substitute."

Amen.

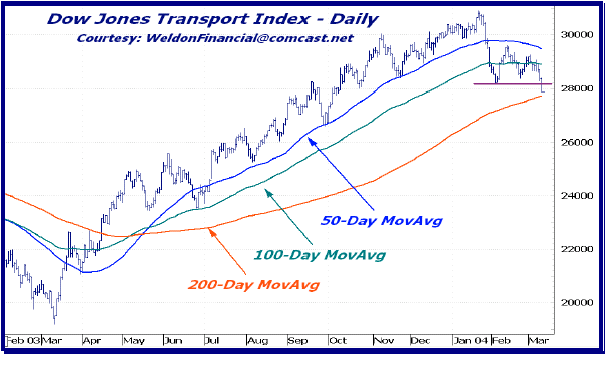

...And then the Transports

...And then the Transports

Going forward, though, what to expect? All things being equal, the dollar will find its "fair value," maybe not in a day, a week, or a month. But sooner rather than letter.

What's striking about this batch of data is that a weaker dollar is not helping U.S. exports on a net basis, especially in that place where it should be helping U.S. exporters most, Europe. I look around me, however, and I don't see Brits lining up to buy U.S.-made products that are cheaper now then they were a year ago. Software wasn't flying off the shelves. Nor were Brittany Spears CDs.

This leads me to believe that if a weaker dollar is really going to reduce the deficit, it will have to be because the price of imports in the U.S. is higher and Americans buy less (it's possible in theory, you know.) The rising price of imports in the U.S. will lower consumption.

And of course, if that happens, it means consumer retrenchment...and a slower economic growth--which certainly isn't good for the dollar either.

The hard truth is there's no way out of a weaker dollar adjustment. Try as you might, the math simply doesn't add up. It can be resisted, ignored, and mocked. But it can't be denied. And it will start showing up in the figures of foreign purchases of U.S. assets...if the government ever gets around to publishing them again (sort of like the PPI numbers.)

Going forward, though, what to expect? All things being equal, the dollar will find its "fair value," maybe not in a day, a week, or a month. But sooner rather than letter.

What's striking about this batch of data is that a weaker dollar is not helping U.S. exports on a net basis, especially in that place where it should be helping U.S. exporters most, Europe. I look around me, however, and I don't see Brits lining up to buy U.S.-made products that are cheaper now then they were a year ago. Software wasn't flying off the shelves. Nor were Brittany Spears CDs.

This leads me to believe that if a weaker dollar is really going to reduce the deficit, it will have to be because the price of imports in the U.S. is higher and Americans buy less (it's possible in theory, you know.) The rising price of imports in the U.S. will lower consumption.

And of course, if that happens, it means consumer retrenchment...and a slower economic growth--which certainly isn't good for the dollar either.

The hard truth is there's no way out of a weaker dollar adjustment. Try as you might, the math simply doesn't add up. It can be resisted, ignored, and mocked. But it can't be denied. And it will start showing up in the figures of foreign purchases of U.S. assets...if the government ever gets around to publishing them again (sort of like the PPI numbers.)