The good news today is that even though corporate layoffs were up in January 26% to 117,556, that was 11% lower than January 2003's 132,222 and 53% lower than January 2002's 248,475.

But does that mean the employment picture is improving because there are fewer layoffs? We'll have a better idea when Friday's numbers come out. But it's an important question for stock investors.

Increased business hiring is crucial to a strong recovery. Business spending creates consumer incomes. And a consumer who makes money spends more money.

An early sign of future business hiring is increased business investment. If businesses are investing, it traditionally means hiring will soon follow. But something may be different about this economic environment. We may see higher business investing WITHOUT the employment. That's because

current business investment is in exactly those areas than tend to reduce jobs, not create them.

Take the two charts below for example. The first shows business investment over the last four years. You can see it topped out right before the stock market in early 200. It's begun to recover since early 2002. And in the fourth quarter, it was again up a respectable 6.9%, surely an encouraging sign for employment right?

Maybe not. The second chart shows investment in equipment and software as a percentage of business investment (as opposed to investment in structures.) In 2000, equipment and software investment ($918 billion) were 74% of total business investment more than twice business investment in "structures." In 2003, equipment and software grew to 79% of total investment.

Business investment is recovering gradually...

...but does investment in equipment and software create jobs?

...but does investment in equipment and software create jobs?

It's obvious from these numbers that equipment and software investment makes up the bulk of business investment. It's been that way for some time. But what is included in the category "equipment and software?" The answer can be found in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). And what you'll find is that a large percentage of American business investment is in information technology...and that this is almost certainly bad news for the labor market.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis has put the data for GDP into a format that's searchable and exportable. (God bless Dr. Richebacher, who's been working off hard copies all these years.) That makes it easy for you to breakdown exactly where business investment is taking place and then try and correlate that with trends in the labor market.

The NIPA numbers show four distinct categories of equipment and software investment. They are: information technology, industrial, transportation, and other. I've gone back over the last fifteen years and looked at the changes in the composition of the equipment and software numbers to see what they show us.

First, a table showing what percentage each category is of total equipment and software investment in 1990 and then in 2000

% of Equipment and Software Investment

1990 2000

Info Tech. 41% 50%

Industrial 21% 17%

Transportation 16% 17%

Other 19% 14%

As you can see, IT spending was already the leading component of business investment in 1990. By 2000, it had grown another 10%, while investment in the "old economy" declined 4%. In terms of actual dollars...IT spending grew 163% between 1990 and 2000. "Old Economy" spending grew at less than half rate, 72%.

And in third quarter of last year when total business investment grew at 12.8%, investment in equipment and software actually grew at 17.6%, making up for the actual decline in business structure investment. Within the equipment and software category, it was computers and software that accounted for the largest gain at 27%, while transportation investment actually shrunk, and investment in "old economy" industrial equipment grew at 1.5%.

Machines Replace Men

Greenspan likes to argue that business investment in IT makes us more productive, and that rising productivity is the hallmark of a growing economy with rising standards of living. He admits that it causes "dislocations." As businesses by labor saving devices, some workers get more productive. The rest get laid off. The Chairman, however, is not too concerned. Our economy is dynamic. I'll quote him at length from a recent speech delivered via satellite to the HM Treasury Enterprise Conference in London on January 26th. Emphasis added is mine.

"...Starting in the 1970s, American Presidents, supported by bipartisan majorities in the Congress, deregulated large segments of the transportation, communications, energy, and financial services industries. The stated purpose was to enhance competition, which was increasingly seen as a spur to productivity growth and elevated standards of living...."

"As a consequence, the United States, then widely seen as a once great economic power that had lost its way, gradually moved back to the forefront of what Joseph Schumpeter, the renowned Harvard professor, called "creative destruction," the continuous scrapping of old technologies to make way for the innovative.

In that paradigm, standards of living rise because depreciation and other cash flows of industries employing older, increasingly obsolescent, technologies are marshaled, along with new savings, to finance the production of capital assets that almost always embody cutting-edge technologies. Workers, of necessity, migrate with the capital."

So far so good. Old industries die out. New ones with newer technologies are born. And with them, new jobs. At least that's the theory. Greenspan is just heating up.

He continues, "Through this process, wealth is created, incremental step by incremental step, as high levels of productivity associated with

innovative technologies displace lesser productive capabilities. The model presupposes the continuous churning of a flexible economy in which the new displaces the old."

That "displacement," of course, is the loss of jobs in old industries. It DOES create new wealth in the new industries where it creates new employment. However that wealth need not be created in America. American providers of IT goods and services will make a profit. But much of their labor may come from overseas. And of course, non-American companies selling IT goods and services will make a profit too.

Greenspan does admit that this focus on IT investment creates what he calls a "structural" labor problem. We focus on what our workers have a comparative advantage in and are more productive in (technology) and invest less in areas where we're not as competitive. He says, "In recent years, competition from abroad has risen to a point at which developed countries' lowest skilled workers are being priced out of the global market place."

That's Fed-speak for losing your job because it's cheaper to do overseas. All of which is fine. That's what happens in mostly free globalized markets. If you believe in free markets you have to take your medicine on this one. But it does raise the question of where the new jobs will come from, a question I've often asked here.

Where will American enjoy a comparative advantage in the 21st century? It certainly promises to be bright if you're information and technology savy and provide a service that depends on personal experience and judgment. But even white collar jobs are becoming commodified. Not to worry, says the Chairman.

"We can usually identify somewhat in advance which tasks are most vulnerable to being displaced by foreign or domestic competition.

But in economies at the forefront of technology, most new jobs are the consequence of innovation, which by its nature is not easily predictable."

That doesn't stop him from trying though, "

What we in the United States do know is that, over the years, more than 94% of our workforce, on average, has been employed as markets matched idled workers seeking employment to new jobs. We can thus be confident that new jobs will displace old ones as they always have, but not without a high degree of pain for those caught in the job-losing segment of America's massive job turnover process."

Trouble is, new jobs AREN'T replacing the old ones, Greenspan's assurances aside. And we can't really say in this brave new world if they will. Even the Fed's own researchers aren't sure. Here's a quotation from a January study in "

The Regional Economist," a publication of the St. Louis Fed.

"The second type of labor market turnover is more permanent, what economists call "structural" job losses or gains. Structural unemployment occurs, for example, when new technologies lead to new labor-saving production processes or lead to new types of goods and services that replace existing products. In manufacturing and agriculture, for instance, industries have continually taken advantage of technological innovations that have lessened their demand for labor. The result is that fewer workers are needed to produce the same amount of output, and the firms and workers who remain in these industries are more productive.

"For example, from 1992 to 2002, the number of motor vehicles produced in the United States rose from 9.7 million to 12.5 million, while the number of production workers declined by about 5 percent to 222,000. "Big-box" retailers like Sam's, Costco and Best Buy have fueled dramatic changes in the distribution and warehousing of goods. The information technology revolution has played an important role in this retail revolution.2 Although structural changes tend not to be the cause of recessions, they may nonetheless be a contributing factor to a jobless recovery."

What does a structural change to the job look like? Take a look at the chart below. You can find the whole report

here.

Greenspan could be right. Maybe the jobs will come. And if they do come, and if they are driven by technology, maybe we simply can't know what they are until they get here. After all, who would have guessed the people below would go on to create so much wealth for investors and productivity for business?

Still, all the evidence points to an America with excellent technology and high-paying jobs. And I haven't explored how rising productivity helps the whole work force. But in the shorter-term, a lot more Americans are going to be "displaced" under globalization. They already don't' like it. They'll like it even less as the pace picks up.

In fact, they may like it so little that their lackey politicians start clamoring for trade restrictions...oh wait...that's already happening.

By the way, if you're a data junkie like me, you may be interested to know that the last year in which business investment in industrial goods exceeded IT investment was 1977.

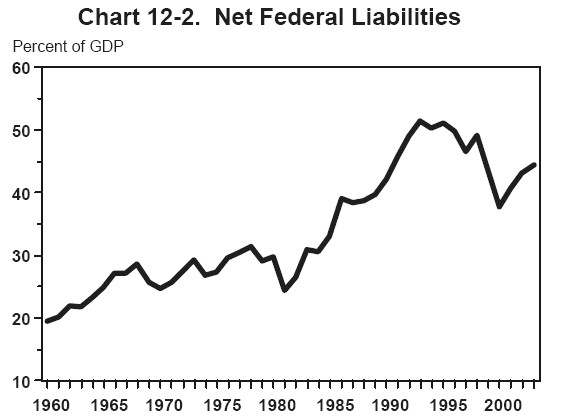

The government explanation for what a "liability" is.

Table 12-1 includes Federal liabilities that would also be listed on a business balance sheet. All the various forms of publicly held Federal debt are counted, as are Federal pension and health insurance obligations to civilian and military retirees and the disability compensation that is owed the Nation's veterans. The estimated liabilities stemming from Federal insurance programs and loan guarantees are also shown. The benefits that are due and payable under various Federal programs are also included, but these are short-term obligations not long-term responsibilities. Other obligations, including future benefit payments that are likely to be made through Social Security and other Federal income transfer programs, are not shown in this table. These are not Federal liabilities in a legal or accounting sense. They are Federal responsibilities, and it is important to gauge their size, but they are not binding in the same way that a liability is.

The government explanation for what a "liability" is.

Table 12-1 includes Federal liabilities that would also be listed on a business balance sheet. All the various forms of publicly held Federal debt are counted, as are Federal pension and health insurance obligations to civilian and military retirees and the disability compensation that is owed the Nation's veterans. The estimated liabilities stemming from Federal insurance programs and loan guarantees are also shown. The benefits that are due and payable under various Federal programs are also included, but these are short-term obligations not long-term responsibilities. Other obligations, including future benefit payments that are likely to be made through Social Security and other Federal income transfer programs, are not shown in this table. These are not Federal liabilities in a legal or accounting sense. They are Federal responsibilities, and it is important to gauge their size, but they are not binding in the same way that a liability is.

The dollar matters a lot more to stock prices now than any single factor. That's why I'm spending so much time trying to make it clear that sometime this year, you're going to hear the dollar break, and it's going to start costing Americans in ways they can't imagine.

Here's a quote from a Dallas Fed report on the risks to the economy in 2004. You can find the whole report at http://www.dallasfed.org/research/indepth/2004/id0401.html . The big risk is that the weak dollar leads to a sell-off in U.S. financial assets AND a powerful surge in inflation. Which means you'll wake up one day and find that your latte is 40% more expensive.

"...a disorderly decline in the dollar could boost inflation fears and bond yields, thereby undoing some of the financial stimulus to housing, consumption, and investment. Currently, foreigners are lending an extra $1.5 billion a day to the U.S., much of which is in the form of central bank purchases of U.S. Treasuries."

It's not just a fall in stock prices that a weak dollar prompts...but a rise wholesale and consumer prices. The study continues:

The dollar could plunge if private investment sentiment shifted suddenly against investing in U.S. assets or if some foreign central banks buy less Treasury debt to keep their currencies from rising against the dollar. The dollar matters partly because a sudden decline could push up non-oil import prices (shown by the red line in Figure 12), which have an influence on core wholesale prices at the intermediate level (the blue line).

The dollar matters a lot more to stock prices now than any single factor. That's why I'm spending so much time trying to make it clear that sometime this year, you're going to hear the dollar break, and it's going to start costing Americans in ways they can't imagine.

Here's a quote from a Dallas Fed report on the risks to the economy in 2004. You can find the whole report at http://www.dallasfed.org/research/indepth/2004/id0401.html . The big risk is that the weak dollar leads to a sell-off in U.S. financial assets AND a powerful surge in inflation. Which means you'll wake up one day and find that your latte is 40% more expensive.

"...a disorderly decline in the dollar could boost inflation fears and bond yields, thereby undoing some of the financial stimulus to housing, consumption, and investment. Currently, foreigners are lending an extra $1.5 billion a day to the U.S., much of which is in the form of central bank purchases of U.S. Treasuries."

It's not just a fall in stock prices that a weak dollar prompts...but a rise wholesale and consumer prices. The study continues:

The dollar could plunge if private investment sentiment shifted suddenly against investing in U.S. assets or if some foreign central banks buy less Treasury debt to keep their currencies from rising against the dollar. The dollar matters partly because a sudden decline could push up non-oil import prices (shown by the red line in Figure 12), which have an influence on core wholesale prices at the intermediate level (the blue line).

The Fed report says the stage is set for a robust recovery, but that there are some remaining "headwinds." The dollar is the biggest one. What's interesting is how important business investing is to the tone of the report. And within business investing, the report mentions exactly the same subject I looked at yesterday, IT and software spending.

"Looking within manufacturing, virtually all the increase in output has occurred in the high-tech sector, depicted by the blue line in Figure 5, with recent signs that output excluding high tech; the red line;has begun increasing. The revival in high tech reflects the combination of a rebound in business equipment investment and increased high-tech sales to consumers."

Manufacturing output because business investment in IT is up. So shows the chart below. But it hasn't yet led to higher employment. And as I contended yesterday, it might not at all. Changes in the labor market don't take place within just the U.S. economy any more. They take place in a globalized workforce, where the division of labor is global. There's no guarantee that lost jobs in one domestic field will lead to new jobs in a new domestic field.

The Fed report says the stage is set for a robust recovery, but that there are some remaining "headwinds." The dollar is the biggest one. What's interesting is how important business investing is to the tone of the report. And within business investing, the report mentions exactly the same subject I looked at yesterday, IT and software spending.

"Looking within manufacturing, virtually all the increase in output has occurred in the high-tech sector, depicted by the blue line in Figure 5, with recent signs that output excluding high tech; the red line;has begun increasing. The revival in high tech reflects the combination of a rebound in business equipment investment and increased high-tech sales to consumers."

Manufacturing output because business investment in IT is up. So shows the chart below. But it hasn't yet led to higher employment. And as I contended yesterday, it might not at all. Changes in the labor market don't take place within just the U.S. economy any more. They take place in a globalized workforce, where the division of labor is global. There's no guarantee that lost jobs in one domestic field will lead to new jobs in a new domestic field.

My colleague James Boric summed up--with a lot more efficiency--the argument he saw me making: "What you are saying is...Sure, US companies may continue to invest in new equipmentnt. And in fact they might keep on coming up with the best new inventions -- that revolutionize the world. And yes, those will create new opportunitieses for workers. But it isn't likely that those jobs will be filled in the US. It would be cheaper for Intel, Microsoft and Cicso to farm out their work to Mexican or Chinese workers -- who will do the same job but for 40% less. As we become more and more technologically advanced, our machines will actually replace the need for manpower -- just like mechanized farming equipment did in the 1900s."

Jamedisagreesss with me and sides with the chairman that the key issue is flexibility...and that even though we can't know what the next big thing will be that creates new jobs, there's always been one...from the railroads, to cars, to computers.

Maybe.

But maybe it's not a bad time to prepare yourself for a world in which all but the very best jobs migrate outside America to places where they can be done more cheaply. It's another great migration. But this time it's not to America, or even within America. It's the great migration of the world economy from the West to East...the services production capital of the world in India and the goods production capital of the world China.

It's a great economic contest. And America does have some economic advantages, technology being one of them. But it's also a contest for basic natural resources. As a reviewer for a book I'm reading on China put it,

"Can the Earth sustain yet another industrialized and consumption-based economy in a country with a population nearly four times that of the U.S.? Are Americans and other Westernized countries willing to relinquish some of the standard of living increases made in the past few decades to meet the growing resource demands of such international development?"

You don't have to relinquish a high standard of living. You just have to prepare for the events coming. One way of doing that is to realize the gravity of the threat. Just doing that will make you much more realistic about what you have to do as an investor.

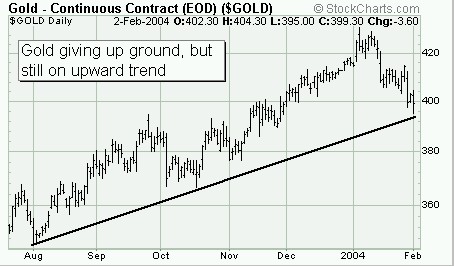

And after that...you can pursue the path I've laid out in SI...profiting on the delcine of the financial economy (sometimes with leverage if you can afford the risk). Owning the assets of countries on the periphery of the Asian boom through exchange traded funds. And of course, in an age of self-immolating paper currencies, own gold.

My colleague James Boric summed up--with a lot more efficiency--the argument he saw me making: "What you are saying is...Sure, US companies may continue to invest in new equipmentnt. And in fact they might keep on coming up with the best new inventions -- that revolutionize the world. And yes, those will create new opportunitieses for workers. But it isn't likely that those jobs will be filled in the US. It would be cheaper for Intel, Microsoft and Cicso to farm out their work to Mexican or Chinese workers -- who will do the same job but for 40% less. As we become more and more technologically advanced, our machines will actually replace the need for manpower -- just like mechanized farming equipment did in the 1900s."

Jamedisagreesss with me and sides with the chairman that the key issue is flexibility...and that even though we can't know what the next big thing will be that creates new jobs, there's always been one...from the railroads, to cars, to computers.

Maybe.

But maybe it's not a bad time to prepare yourself for a world in which all but the very best jobs migrate outside America to places where they can be done more cheaply. It's another great migration. But this time it's not to America, or even within America. It's the great migration of the world economy from the West to East...the services production capital of the world in India and the goods production capital of the world China.

It's a great economic contest. And America does have some economic advantages, technology being one of them. But it's also a contest for basic natural resources. As a reviewer for a book I'm reading on China put it,

"Can the Earth sustain yet another industrialized and consumption-based economy in a country with a population nearly four times that of the U.S.? Are Americans and other Westernized countries willing to relinquish some of the standard of living increases made in the past few decades to meet the growing resource demands of such international development?"

You don't have to relinquish a high standard of living. You just have to prepare for the events coming. One way of doing that is to realize the gravity of the threat. Just doing that will make you much more realistic about what you have to do as an investor.

And after that...you can pursue the path I've laid out in SI...profiting on the delcine of the financial economy (sometimes with leverage if you can afford the risk). Owning the assets of countries on the periphery of the Asian boom through exchange traded funds. And of course, in an age of self-immolating paper currencies, own gold.

...but does investment in equipment and software create jobs?

...but does investment in equipment and software create jobs?

It's obvious from these numbers that equipment and software investment makes up the bulk of business investment. It's been that way for some time. But what is included in the category "equipment and software?" The answer can be found in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). And what you'll find is that a large percentage of American business investment is in information technology...and that this is almost certainly bad news for the labor market.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis has put the data for GDP into a format that's searchable and exportable. (God bless Dr. Richebacher, who's been working off hard copies all these years.) That makes it easy for you to breakdown exactly where business investment is taking place and then try and correlate that with trends in the labor market.

The NIPA numbers show four distinct categories of equipment and software investment. They are: information technology, industrial, transportation, and other. I've gone back over the last fifteen years and looked at the changes in the composition of the equipment and software numbers to see what they show us.

First, a table showing what percentage each category is of total equipment and software investment in 1990 and then in 2000

% of Equipment and Software Investment

1990 2000

Info Tech. 41% 50%

Industrial 21% 17%

Transportation 16% 17%

Other 19% 14%

As you can see, IT spending was already the leading component of business investment in 1990. By 2000, it had grown another 10%, while investment in the "old economy" declined 4%. In terms of actual dollars...IT spending grew 163% between 1990 and 2000. "Old Economy" spending grew at less than half rate, 72%.

And in third quarter of last year when total business investment grew at 12.8%, investment in equipment and software actually grew at 17.6%, making up for the actual decline in business structure investment. Within the equipment and software category, it was computers and software that accounted for the largest gain at 27%, while transportation investment actually shrunk, and investment in "old economy" industrial equipment grew at 1.5%.

Machines Replace Men

Greenspan likes to argue that business investment in IT makes us more productive, and that rising productivity is the hallmark of a growing economy with rising standards of living. He admits that it causes "dislocations." As businesses by labor saving devices, some workers get more productive. The rest get laid off. The Chairman, however, is not too concerned. Our economy is dynamic. I'll quote him at length from a recent speech delivered via satellite to the HM Treasury Enterprise Conference in London on January 26th. Emphasis added is mine.

"...Starting in the 1970s, American Presidents, supported by bipartisan majorities in the Congress, deregulated large segments of the transportation, communications, energy, and financial services industries. The stated purpose was to enhance competition, which was increasingly seen as a spur to productivity growth and elevated standards of living...."

"As a consequence, the United States, then widely seen as a once great economic power that had lost its way, gradually moved back to the forefront of what Joseph Schumpeter, the renowned Harvard professor, called "creative destruction," the continuous scrapping of old technologies to make way for the innovative. In that paradigm, standards of living rise because depreciation and other cash flows of industries employing older, increasingly obsolescent, technologies are marshaled, along with new savings, to finance the production of capital assets that almost always embody cutting-edge technologies. Workers, of necessity, migrate with the capital."

So far so good. Old industries die out. New ones with newer technologies are born. And with them, new jobs. At least that's the theory. Greenspan is just heating up.

He continues, "Through this process, wealth is created, incremental step by incremental step, as high levels of productivity associated with innovative technologies displace lesser productive capabilities. The model presupposes the continuous churning of a flexible economy in which the new displaces the old."

That "displacement," of course, is the loss of jobs in old industries. It DOES create new wealth in the new industries where it creates new employment. However that wealth need not be created in America. American providers of IT goods and services will make a profit. But much of their labor may come from overseas. And of course, non-American companies selling IT goods and services will make a profit too.

Greenspan does admit that this focus on IT investment creates what he calls a "structural" labor problem. We focus on what our workers have a comparative advantage in and are more productive in (technology) and invest less in areas where we're not as competitive. He says, "In recent years, competition from abroad has risen to a point at which developed countries' lowest skilled workers are being priced out of the global market place."

That's Fed-speak for losing your job because it's cheaper to do overseas. All of which is fine. That's what happens in mostly free globalized markets. If you believe in free markets you have to take your medicine on this one. But it does raise the question of where the new jobs will come from, a question I've often asked here.

Where will American enjoy a comparative advantage in the 21st century? It certainly promises to be bright if you're information and technology savy and provide a service that depends on personal experience and judgment. But even white collar jobs are becoming commodified. Not to worry, says the Chairman.

"We can usually identify somewhat in advance which tasks are most vulnerable to being displaced by foreign or domestic competition. But in economies at the forefront of technology, most new jobs are the consequence of innovation, which by its nature is not easily predictable."

That doesn't stop him from trying though, "What we in the United States do know is that, over the years, more than 94% of our workforce, on average, has been employed as markets matched idled workers seeking employment to new jobs. We can thus be confident that new jobs will displace old ones as they always have, but not without a high degree of pain for those caught in the job-losing segment of America's massive job turnover process."

Trouble is, new jobs AREN'T replacing the old ones, Greenspan's assurances aside. And we can't really say in this brave new world if they will. Even the Fed's own researchers aren't sure. Here's a quotation from a January study in "

It's obvious from these numbers that equipment and software investment makes up the bulk of business investment. It's been that way for some time. But what is included in the category "equipment and software?" The answer can be found in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA). And what you'll find is that a large percentage of American business investment is in information technology...and that this is almost certainly bad news for the labor market.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis has put the data for GDP into a format that's searchable and exportable. (God bless Dr. Richebacher, who's been working off hard copies all these years.) That makes it easy for you to breakdown exactly where business investment is taking place and then try and correlate that with trends in the labor market.

The NIPA numbers show four distinct categories of equipment and software investment. They are: information technology, industrial, transportation, and other. I've gone back over the last fifteen years and looked at the changes in the composition of the equipment and software numbers to see what they show us.

First, a table showing what percentage each category is of total equipment and software investment in 1990 and then in 2000

% of Equipment and Software Investment

1990 2000

Info Tech. 41% 50%

Industrial 21% 17%

Transportation 16% 17%

Other 19% 14%

As you can see, IT spending was already the leading component of business investment in 1990. By 2000, it had grown another 10%, while investment in the "old economy" declined 4%. In terms of actual dollars...IT spending grew 163% between 1990 and 2000. "Old Economy" spending grew at less than half rate, 72%.

And in third quarter of last year when total business investment grew at 12.8%, investment in equipment and software actually grew at 17.6%, making up for the actual decline in business structure investment. Within the equipment and software category, it was computers and software that accounted for the largest gain at 27%, while transportation investment actually shrunk, and investment in "old economy" industrial equipment grew at 1.5%.

Machines Replace Men

Greenspan likes to argue that business investment in IT makes us more productive, and that rising productivity is the hallmark of a growing economy with rising standards of living. He admits that it causes "dislocations." As businesses by labor saving devices, some workers get more productive. The rest get laid off. The Chairman, however, is not too concerned. Our economy is dynamic. I'll quote him at length from a recent speech delivered via satellite to the HM Treasury Enterprise Conference in London on January 26th. Emphasis added is mine.

"...Starting in the 1970s, American Presidents, supported by bipartisan majorities in the Congress, deregulated large segments of the transportation, communications, energy, and financial services industries. The stated purpose was to enhance competition, which was increasingly seen as a spur to productivity growth and elevated standards of living...."

"As a consequence, the United States, then widely seen as a once great economic power that had lost its way, gradually moved back to the forefront of what Joseph Schumpeter, the renowned Harvard professor, called "creative destruction," the continuous scrapping of old technologies to make way for the innovative. In that paradigm, standards of living rise because depreciation and other cash flows of industries employing older, increasingly obsolescent, technologies are marshaled, along with new savings, to finance the production of capital assets that almost always embody cutting-edge technologies. Workers, of necessity, migrate with the capital."

So far so good. Old industries die out. New ones with newer technologies are born. And with them, new jobs. At least that's the theory. Greenspan is just heating up.

He continues, "Through this process, wealth is created, incremental step by incremental step, as high levels of productivity associated with innovative technologies displace lesser productive capabilities. The model presupposes the continuous churning of a flexible economy in which the new displaces the old."

That "displacement," of course, is the loss of jobs in old industries. It DOES create new wealth in the new industries where it creates new employment. However that wealth need not be created in America. American providers of IT goods and services will make a profit. But much of their labor may come from overseas. And of course, non-American companies selling IT goods and services will make a profit too.

Greenspan does admit that this focus on IT investment creates what he calls a "structural" labor problem. We focus on what our workers have a comparative advantage in and are more productive in (technology) and invest less in areas where we're not as competitive. He says, "In recent years, competition from abroad has risen to a point at which developed countries' lowest skilled workers are being priced out of the global market place."

That's Fed-speak for losing your job because it's cheaper to do overseas. All of which is fine. That's what happens in mostly free globalized markets. If you believe in free markets you have to take your medicine on this one. But it does raise the question of where the new jobs will come from, a question I've often asked here.

Where will American enjoy a comparative advantage in the 21st century? It certainly promises to be bright if you're information and technology savy and provide a service that depends on personal experience and judgment. But even white collar jobs are becoming commodified. Not to worry, says the Chairman.

"We can usually identify somewhat in advance which tasks are most vulnerable to being displaced by foreign or domestic competition. But in economies at the forefront of technology, most new jobs are the consequence of innovation, which by its nature is not easily predictable."

That doesn't stop him from trying though, "What we in the United States do know is that, over the years, more than 94% of our workforce, on average, has been employed as markets matched idled workers seeking employment to new jobs. We can thus be confident that new jobs will displace old ones as they always have, but not without a high degree of pain for those caught in the job-losing segment of America's massive job turnover process."

Trouble is, new jobs AREN'T replacing the old ones, Greenspan's assurances aside. And we can't really say in this brave new world if they will. Even the Fed's own researchers aren't sure. Here's a quotation from a January study in " Greenspan could be right. Maybe the jobs will come. And if they do come, and if they are driven by technology, maybe we simply can't know what they are until they get here. After all, who would have guessed the people below would go on to create so much wealth for investors and productivity for business?

Still, all the evidence points to an America with excellent technology and high-paying jobs. And I haven't explored how rising productivity helps the whole work force. But in the shorter-term, a lot more Americans are going to be "displaced" under globalization. They already don't' like it. They'll like it even less as the pace picks up.

In fact, they may like it so little that their lackey politicians start clamoring for trade restrictions...oh wait...that's already happening.

Greenspan could be right. Maybe the jobs will come. And if they do come, and if they are driven by technology, maybe we simply can't know what they are until they get here. After all, who would have guessed the people below would go on to create so much wealth for investors and productivity for business?

Still, all the evidence points to an America with excellent technology and high-paying jobs. And I haven't explored how rising productivity helps the whole work force. But in the shorter-term, a lot more Americans are going to be "displaced" under globalization. They already don't' like it. They'll like it even less as the pace picks up.

In fact, they may like it so little that their lackey politicians start clamoring for trade restrictions...oh wait...that's already happening.

By the way, if you're a data junkie like me, you may be interested to know that the last year in which business investment in industrial goods exceeded IT investment was 1977.

By the way, if you're a data junkie like me, you may be interested to know that the last year in which business investment in industrial goods exceeded IT investment was 1977.